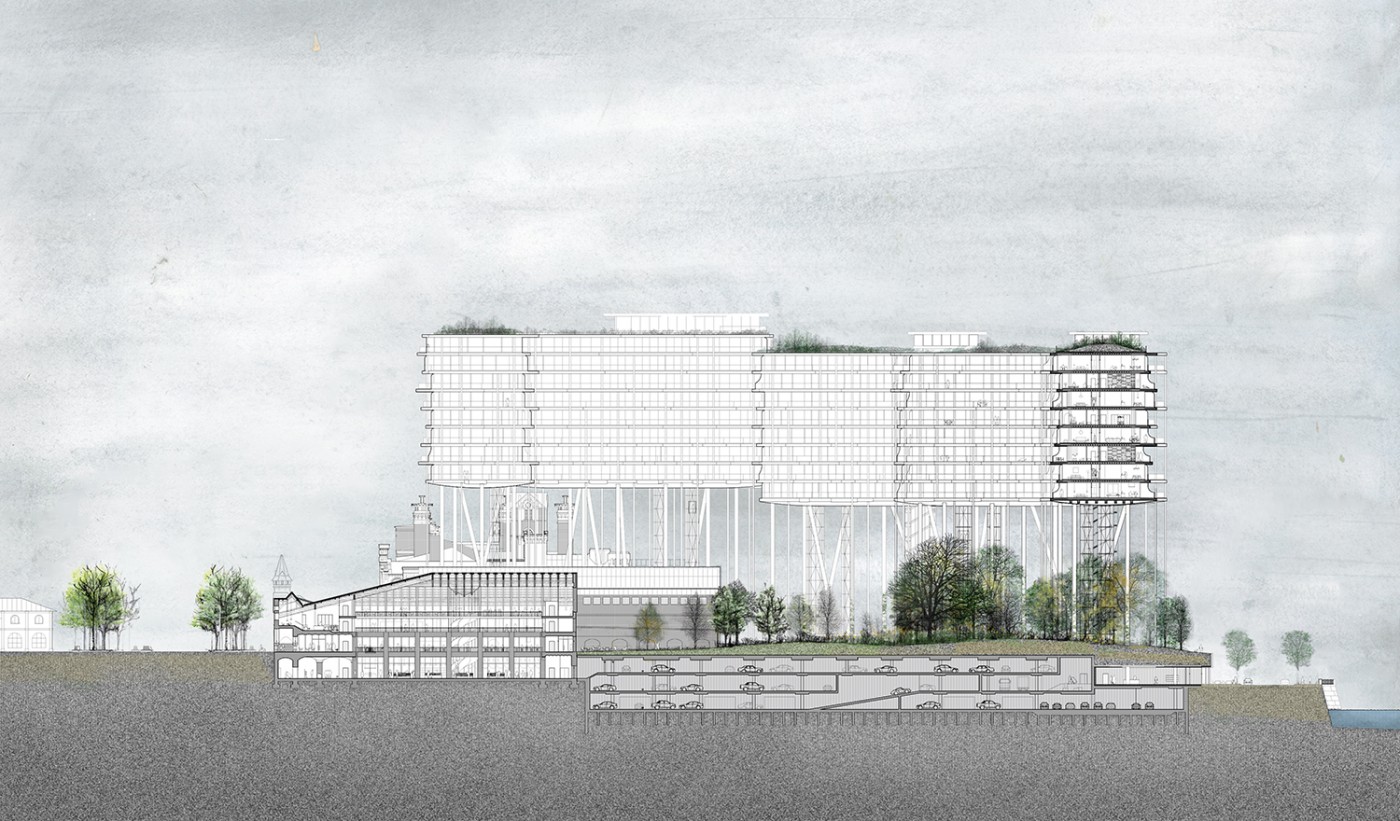

Located along the Moskva River, the partially dilapidated site of the historic Badaevskiy Brewery is being rehabilitated into a mixed-use public area in central Moscow–with recreational, commercial, and residential facilities. While the heritage buildings of the factory are being restored, a large residential complex is added. It sits lifted 35 meters above ground on a forest of columns. Underneath, at the heart of the development, a 6 ha area is becoming a new neighborhood park for Moscow. Situated atop a 400 m stretch of elevated river embankment, this man-made tract sets the stage for a condensed interpretation of the East European mixed forest. Informed by an understanding of the natural processes that define a forest edge, the park is structured as a succession of layers culminating in an open orchard that recalls Moscow’s historic parks and reinforces the collective memory of the city.

Two Landscape Types as Reference

The project responds to this cultural dimension by integrating two landscape types that bear a literary significance in Russian collective memory: the soft edge of primary succession, affectionately called the opushka, and the flowering orchard. In the Russian imagination, the opushka carries poetic associative connotations of benign wilderness, softness, abundance, and warmth. In cultivated landscapes, this exuberance is translated into the form of productive orchards. In Moscow, orchards were historically planted near the river’s edge, as in Kolomenskoje, where people still collect fruit, or the apple trees planted in the 1950s along Kutuzovsky Avenue, just 4 kilometers away from the site.

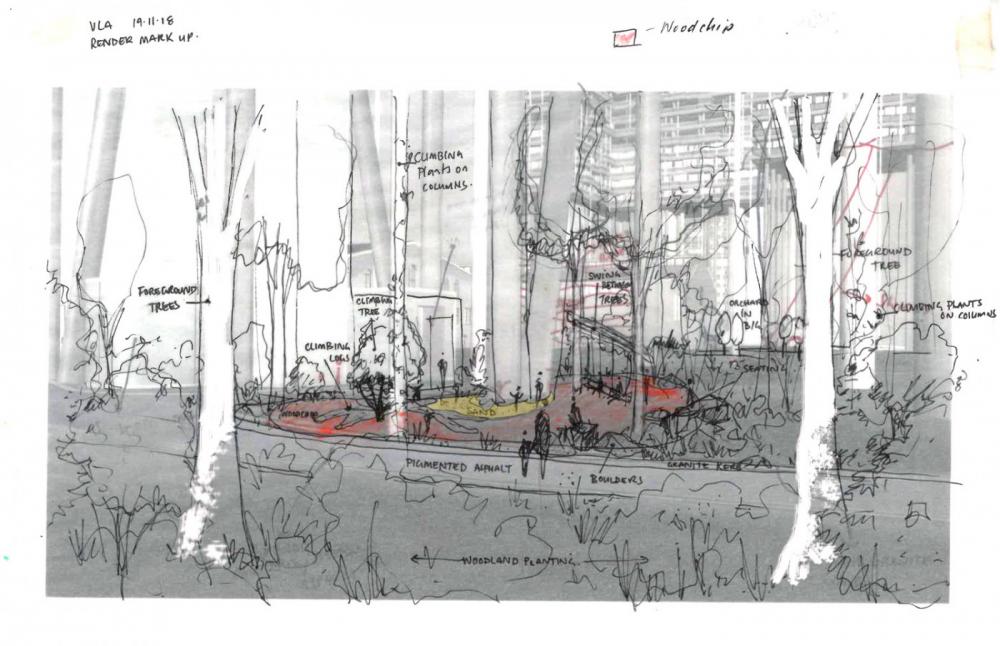

Translation into a Layered Design

The “forest edge” provides a layered spatial structure that articulates the relation between existing and new elements—the heritage factory building, the new architecture with its ultimate level of private garden rooftops, and the river bank. At the exterior, the embankment’s hard edge is modulated by smaller sun-loving plants and forms the interface with the river. Inside the shaded forest interior, 20 m tall trees merge with the massive columns that lift up the horizontal skyscraper. Gradually, these give way to the opushka, where smaller variegated pioneer species and dense ground cover call to mind natural abundance and diversity. Closer to the interior and lower to the ground, undulating soft meadows finally lead into the grassland where clumps of fruit trees change with the seasons and invite genuine biodiversity into the park year-round.

Altogether, over eighty species make up the planting palette of the park. This diversity of vegetation recalls indigenous mixed forests, while the fruit trees bring the visitors into direct engagement with the landscape. The planting scheme is thus central to the project, as it makes tangible the ever-present connection between culturally constructed notions of “nature” and their inherent qualities of biodiversity and vitality, from which cultural significance in turn arises.

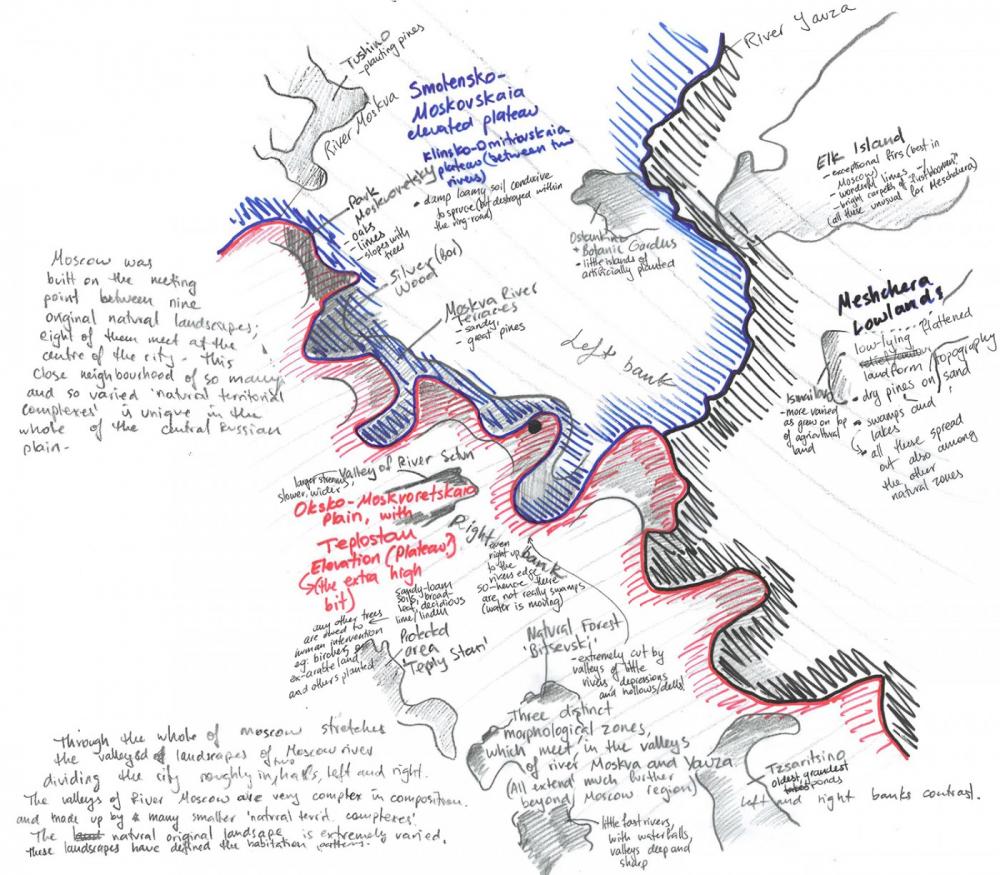

The Metropolitan Landscape of Moscow

Moscow is characterized by a high level of complexity and diversity in both indigenous and anthropogenic landscapes. Established in the twelfth century, the city was built on the ancient alluvial terraces of the Moskva river, at the meeting point of three physiographic provinces that defined its shape: the elevated hilly terrain in the southwest, the low-lying flatter landforms in the northeast, and elevated plains in the northwest. Within these, nine individual territorial complexes—specific combinations of topography, hydrology, soil type, and vegetation—converge at the city center. While such a dense array is unique in the Central Russian Plain, this indigenous landscape has over time been transformed by agriculture, infrastructure, and urban buildup, with a tendency toward the reduction of biodiversity. Indeed, even though original woodlands remain at the outskirts of Moscow, urban vegetation is the result of more than eight hundred years of human activity through the cultivation of monastery gardens, large estates, nurseries, or Soviet cooperatives that have become public parks. These parks form part of the collective memory and culture of the living city.

© Herzog & de Meuron